BOOK FOUR - THE TRAITOR'S NOOSE

England

England

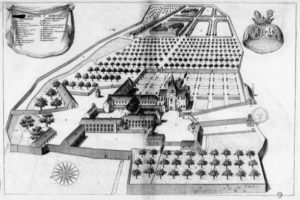

Cambridge Castle, Cambridgeshire

| 1) The remains of Cambridge Castle in the late 18th century. 2) All that remains on the site today. |

| Catherine rested the quill upon the parchment and stood to look out through the open shutters. The day was bright, though a little cold and she stared wistfully at a passing cloud. |

Windsor Palace, Windsor

| Catherine secured her cloak before sliding on the leather gloves. It was only a short walk from the Upper Court of Windsor Castle to the Rose Tower, but the snow lay thick upon the ground and the wind bit into every part of her exposed skin. |

Blackfriars, London

| Blackfriars Road, c. 1870 |

| The corner of Carter Lane and Friar Street, Blackfriars. |

| The Black Friar Pub, today. |

| As Catherine stood in the hallway of Simon's home in Blackfriars, a flood of memories threatened to over come her ... Everything around her was a reminder of Simon - the thread-bare tapestry on the wall, the collection of Moroccan beads above the fireplace and the unfinished game of chaturanga. |

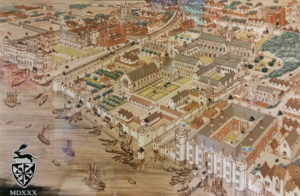

The White Tower, London

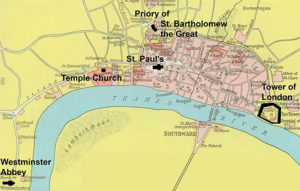

| Artists impression of The White Tower in the 14th century Map of medieval London |

|

Simon considered his surroundings. His apartment was not large. It consisted of two sparsely-furnished rooms - a reception area and private quarters for ablutions and sleeping. Not that he could complain. It was nothing like the cells he had once visited as a child with Charles Marshall.

His father had insisted on seeing John Graham, the Earl of Monteith, before his execution. The prisoner had been filthy, lying on a dirt floor in a chamber infested with rats. Simon had been appalled and the image of the dying man had figured prominently in may of Simon's childhood nightmares.

|

Westminster Palace, London

| Artists impression of Westminster Palace and Westminster Hall c. 14th century |

| Simon was escorted through the side door. He lifted his head and scanned the many faces around him. Peers of the realm, members of the clergy and his family and friends had all converged in one place - the Great Hall of Westminster. |

France

France

Séez

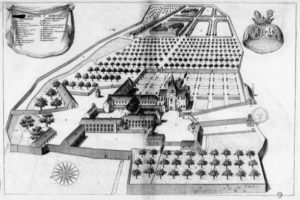

|

|

| The nearby gothic cathedral, remarkable for its stately, twin spires piercing the Heavens, sat eerily quiet. Within the nave, beautifully decorated by a bas-relief depicting scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary, the angelic voices usually raised in melodic song at Morning Prayer, were strangely silent. The only noise to be heard came from the fields behind the abbey. Monks, clothed in the thick, woollen robes of their order, tended the soil, tilling with an almost casual indifference.A band of motley horses stampeded into view, the breeds and sizes ranging from peasant farm ponies to princely stallions. Their riders were no better; some wearing costly steel breastplates while others were padded with simple, leather jerkins. But they were unified in their task, moving as one great beast whose intention it was to devour everything in its path. They halted in front of the cathedral and one man, his armoured chest glinting in the dull sunlight, edged his horse forward just as the bishop emerged to stand beneath the pointed arch. ‘Greetings, Father.’

‘What is the meaning of this unkempt display in front of God’s house?’ The Bishop shooed them back. ‘How dare you sully the steps of God’s house! What do you want?’

|

Bellegarde

| Gillet stabbed the spatchcock with his knife and peeled back the roasted skin. From across the table, Cécile glared at him. He’d returned home to Bellegarde at the end of the month and waited a week before revealing his latest plan. It had not gone well. He took a bite and placed the cooked joint down with an audible sigh, then chewed silently for a few minutes. The tension in the air was tangible and he felt like he was sitting in front of a misfiring cannon, waiting for the boom. |

| Meschin was staring at the gilt-edged painted plaques on the wall above the fireplace. Gillet had commissioned them after Noël. They were four shields in a row, each joined to the next, the emblems of Albret and Holland in the middle, shouldered on either side by Bellegarde and Armagnac. One of Sancerre’s men, Achille de Pouilly, appeared at Meschin’s side and snorted. ‘Think Sancerre knows?’ |

Brignais

| The Brignais keep had been under the eye of Jean de Melun, the Comte de Tancarville, and Jacques de Bourbon, the Comte de la Marche, for a week now, both commissioned by King Jean. The planned siege was underway and all the entrances to the fortification had been systematically blocked, trapping inside the expanding bands of routiers who had grouped together, calling themselves The Great Company, and taken Brignais Castle as their own. |

Lyon

|

|

| The ancient amphitheatre of Lyon was no longer used to hold plays. If it had been, it may have welcomed the originality of new compilations such as the one the dignitaries of the Loire region had just witnessed. Instead, the derelict Roman building was largely ignored by its population with the exception of the rooms beneath. For a few souls, the chambers held a fascination of a different kind. And for some unfortunate others, the amphitheatre encompassed a terrible fear. |

| Gillet tried to keep his panic under control as he was stripped of clothing and left shivering in his braies. Strong hands gripped his ankles and arms and forced them apart until he was splayed over three spiked rollers on a solid board. At one end, his bare feet were manacled into irons, and at the other end, his wrists tied with rope. At his head was a large cylinder which rotated on a central pin, around which the rope coiled. Attached to this roll was a wheel and, when turned, it tightened the ropes and pulled his body over the three spiked rollers to stretch every muscle and sinew to breaking point. |

|

|

| ‘Milord, you cannot walk.’ Pépi kneeled beside Gillet. ‘I will go and bring back help but if a chance comes, you must take it. At the end of this corridor is a latrine room and I heard the guards say the sewage tunnel which runs beneath connects to an old Roman aqueduct which leads directly to the river.’ |

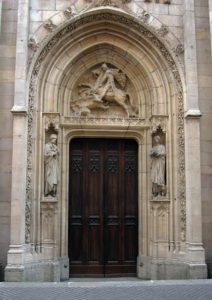

| On the other side was a parish church and beside it a building with two cylindrical towers. A knight carrying a lit sconce passed through a connecting arched portal to alight the steps of the church. He wore a long, black, belted surcotte which blazed an eight-pointed white cross over his breast. By the time Gillet made it to the parish steps, the wounds on his fingers and feet had split open and were bleeding profusely. The knight came out from the chapel and held up his flaming torch with a look of astonishment. Gillet, his face swollen, cut and bruised, reached out a ruined, massacred hand and gasped. ‘For the love of Saint John … help me.’ |

Perpenya, Kingdom of Majorca

(actual photos from a 2016 research trip - CT)

| The palace of the Kings of Majorca sprawled out in front of them. Three massive square courtyards were split by a maze of lush gardens, |

| ...the whole surrounded by walls of uncut stones bound with a mortar and painted. A labyrinth of red brick archways greeted them, some rounded, and some pointed in the current architectural style of Opus Francigenum. |

| ‘What’s that?’ Cécile indicated a huge, spiky tree that looked as though its leaves had all been cut into strips and the bark on its stout trunk was slashed diamond-shaped like a lozenge pattern.

Gillet laughed. ‘I sometimes forget how closeted a life you have led, chérie! It’s a palm tree, sweetheart, from Northern Africa. The further south you travel, the more abundant they become. When I was younger and in service to Simon in Morocco, they had plantations of date palms surrounding the house. |

| The party was invited indoors, out of the hot sun, and directed into the great hall with a huge ribbed and vaulted ceiling where they were given long, cool drinks. |

| The palace had a Middle-Eastern quality with ochre- coloured stone and sandstone, and an abundance of red marble from Spain and blue and white marble from the Pyrénées Mountains. |

| 'The palace has two chapels,’ the man-servant informed them conversationally, ‘one of which is contained in the heart of the royal apartments. |

| The other lies beneath it and you will see it imitates the style of your own beloved Sainte-Chapelle in Paris.’ |

|

| ‘As a little girl, I would love to watch the most exciting bullfights in all Spain, held inside the plaza, right outside our castle walls. The square was surrounded by privately owned homes but the council had the rights to the windows and balconies and for every attraction, they would auction the best seats to the highest bidder. Ah, such glorious times! I would sit and pretend that the most handsome of princes would battle the bulls for my hand. But, in the end, it was a concubine who contracted for me. King Alphonso of Castile kept a beautiful mistress, Leonora, and she wanted power for her son. Alphonso wished to quell the might of the Peñafiel family, so he agreed that my hand should be given to his whore’s son! Me!’ The Comtesse stabbed her chest with her thumb. ‘Heir from the ancient House of Ivrea!’ She fell silent and gazed up at the stars, slowly smiling. ‘And then I met this son and my heart stopped.' |

|

|

| Juana took Cécile’s hand and led her into the chamber where the men were celebrating with cups of wine. Cécile found Gillet sitting at the end of the table, his head bent over a bundle of papers. His fingers were covered in ink and he looked exhausted. |

Carcassonne (Bastide Saint Louis)

| They entered the lower section—the Bastide Saint Louis—just on dusk and above them, set high upon a hill overlooking the river Aude, was one of the jewels in France’s crown—the walled citadel or ‘la cité.’ |

| This older part of Carcassonne consisted of massive Roman towers in cream brick adorned with narrow loop-holes and topped in pointed rose and grey slate caps. Two sets of walls—the outer layer added by the Catholic Crusaders after the expulsion of the heretics known as the Cathars—protected the “old town,” including the “Count’s Castle,” and a church. |

| They rode into the market square and Arnoul d’Audrehem began making inquiries for accommodation. He found a room for Cécile, Minette and the infant with the town’s bailiff and his wife and, for the men, payment secured beds of hay in the loft at the town stables. |

| Above pictures: The actual seneschal's (Baliff) 14thC house. Last Photo: Surviving gate built 1355 - 1359 under the orders of Comte Jean Armagnac.

In front of the bailiff’s house, Gillet dismounted to say goodnight to his wife and kiss Jean Petit. ‘Pa-paa! Pa-paa!’ The little boy held out his arms and Gillet took him. Jean Petit had begun to string words together. ‘Play ball? Play ball?’

'Non, Jean Petit, no ball. Sleep time.’

Jean Petit rubbed his eyes angrily. ‘No sleep!’ he yelled. ‘No!’ He drew back his arm but Gillet held it. ‘No! No hitting.’

|

Larressingle

(Actual photos from a 2006 research trip - CT)

| The ochre and grey stone of Larressingle stood amid the lush, green vineyards. Houses with narrow window slits and arched doorways clustered the protective walls which towered over the moat. Larressingle’s position atop a hill gave it a full view of three hundred and sixty degrees for miles into the distance. A portcullis and small drawbridge guarded the only entrance, the name “Larressingle” derived from “arres sengles, retro singulos” signifying an elevated point which leads to a narrow access, reachable only in single file. |

|

|

| The patch of grass they chose was outside the walls. Cécile settled herself on the rug and stared across the fields. To the left, rows of newly-planted vines were sprouting on a sandy slope, thriving amongst a landscape that was still, for the most part, wild and untamed. Bushes hunched together to create random hedgerows which were protected by large trees.

To the right, a small stone wall ran into the distance, its destination hidden by a thick grove. Behind them, a small lean-to attached to a visitor’s stable provided shade and hid them from prying eyes.

‘Your father is right,’ said Gillet, breaking the silence as he sat beside Cécile. ‘I do have something to tell you.’

‘No, wait!’ Cécile pressed her fingers to Gillet’s mouth. ‘Let me go first, please.’ She took a deep breath. ‘I have held onto something for weeks now, waiting for the right occasion to speak. That moment came and went, and a hundred times since then I have tried to say the words but could not.’

|

|

By mid-afternoon Cécile sat in the church, staring up at the statue of Saint Sigismund, King of Burgundy, to whom the small church in Larressingle was dedicated. Instead, she cast her eyes over the valiant alabaster soldier who died in Orleans in 524AD. The calcite effigy had one foot perched on a rock, body slightly turned with both hands lightly atop the pommel of a sword, the point of the blade resting near his boot. With dignified bearing, he wore a cloak over one shoulder while the tunic beneath was belted with a wide strap of leather and hung to the knees, the lower leg covering crisscrossed with laces. The expression carved into the ancient face was stern and proud.

'Perhaps it is fitting that I should pray to you,’ she whispered. ‘You were a Burgundian taken prisoner and tortured by the King of Orleans whilst my husband, who lives under the lordship of Orleans, was held captive in Burgundy. Such damage has it wrought on his conscience and honour, and upon mine. I know not what to do.’ She stared up at the carven face as though expecting the mouth to move and jumped when a voice answered her. |

|

|

| Jean le Bossu’s house sat opposite the main keep and formed part of the outer wall. He had direct access to one of the towers and on summer evenings he and his wife, Jeanne, would sit atop with a flagon of Gascon wine and drink in the balmy night sky. |

| The house boasted three floors that ran the length of a hall, the bottom level serving as one, surrounded by cream stone walls and beamed ceilings. Outside were two hidden courtyards, tiny but serviceable. It was in one of these that Armand and Cécile waited. |

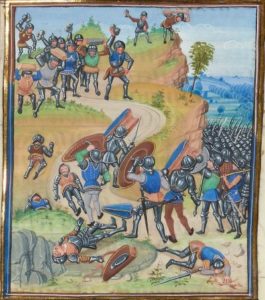

Launac

| The large band of knights in armour pushed through the verge into a clearing, the squire in front holding the Armagnac banner high in the early morning mist. They kept a heavily wooded area on their left as they rode past the village of Launac to find Foix’s men waiting on the far side. |

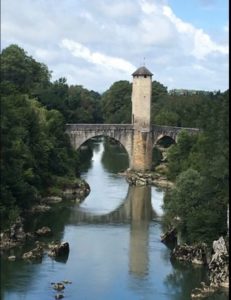

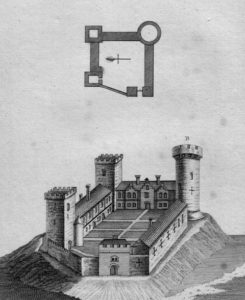

Orthez, Bearn

| The group of captured Armagnacs and Albrets had ridden under guard across the arched stone bridge to the tall watchtower located in the centre, there to wait until Foix’s command allowed them to pass through to the great fortification beyond. Any spark of hope for rescue Gillet had nurtured on their journey to Bearn had been extinguished when he rode over the drawbridge and observed the resourceful layout of Orthez Castle. |

| Unlike most fortifications, the distance between the moat and keep was a steep escarpment so that attackers, having first navigated the stretch of water, would find themselves trapped on a slippery slope that was difficult to climb and left them totally exposed to the projectile defence system. The elliptical path of the enclosure, along with the steepness of the hillside removed any blind spots for the defenders of this impregnable fortress. Invaders would be at the mercy of the loopholes with nowhere to hide. It was pure military genius. |

|

|

| The keep was located in the centre of a courtyard. It was five-sided at the base but became hexagonal at the first level where a north-west spur increased the circular visibility. The walls of the ground floor were pierced by large windows on the northern and southern sides, archer’s niches decorating the stretch between, and connecting to the north tower which housed the guard room. It was here a minor door opened out into a narrow, straight staircase, made inside the curtain wall to connect directly with the dungeon below. The seventy or so steps were lit by two small gaps, mere slits cut into the stone, one to allow what meagre sunlight could penetrate from outside, and the other opening into the guard room itself, to devour the dim rush-light within. |

| Protected by a thick, woollen cloak lined with fur, Gillet extended his arm to his companion as they strolled around the garden, his feet treading lightly on the freshly-fallen blanket of snow. His words, when at length he chose to speak them, were accompanied by puffs of steam. ‘What do you want, Rosslyn?’

‘Want?’ She fluttered her long eyelashes. ‘I have no idea what you mean, Gillet. Is it not divine just to escape my brother’s somewhat outdated ideals of imprisonment and be free to walk in the fresh air? Would you prefer to be back in your cell rather than here with me? I get so bored at Gaston’s castle during winter.’

|

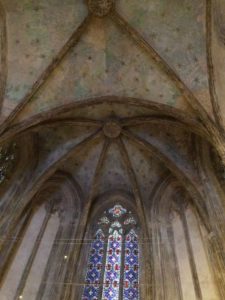

| Above: 13thC church, Saint Pierre, Orthez |

| Above: The beamed ceiling within the church |

| Above: The keystones in Saint Pierre church |

| Gillet looked across to the Saint Pierre church where he had benn allowed a short visit to pray at Yuletide, only he'd spent the entire time staring up at the decorated keystones, wondering what Cécile was doing. |

Tarbes

| Cécile was greeted formally when she arrived at the bastion in Tarbes which she quickly learned was only six leagues from Pau where Foix was currently residing. ‘Tarbes is halfway between Orthez and Larressingle,’ the squire who helped to unload the baggage told her. ‘My master did not wish to inconvenience you.’ He shrugged at her snort for a reply. |

| The two women kept to the path, their feet crunching on the stones as they walked arm-in-arm through the orange grove, the low hum of insects vibrating on the warm air. |

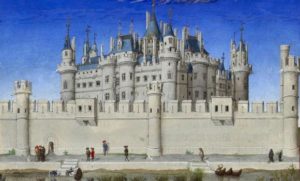

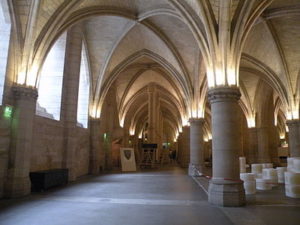

Paris

| 1) The royal palace as seen in Duc de Berri's 'Tres Riche Houres.' 2) The conciergerie and palace with original 14th towers as survives today. |

| The Great Hall (conciergerie) in the royal palace on the Ile de la Cite. |

| Lord and Lady Bellegarde were ushered to a small chamber used as a waiting room to the great hall. The noise emanating from beyond was loud and full of cheer, no doubt aided by the consumption of great quantities of wine. Half the barrels lined up against the wall in the massive kitchen were already empty. Then a herald’s voice echoed up and down the expanse of the hall and a silence fell. A page arrived at the door. ‘It is time. Come, Lord and Lady Bellegarde.’ |

England

England

France

France